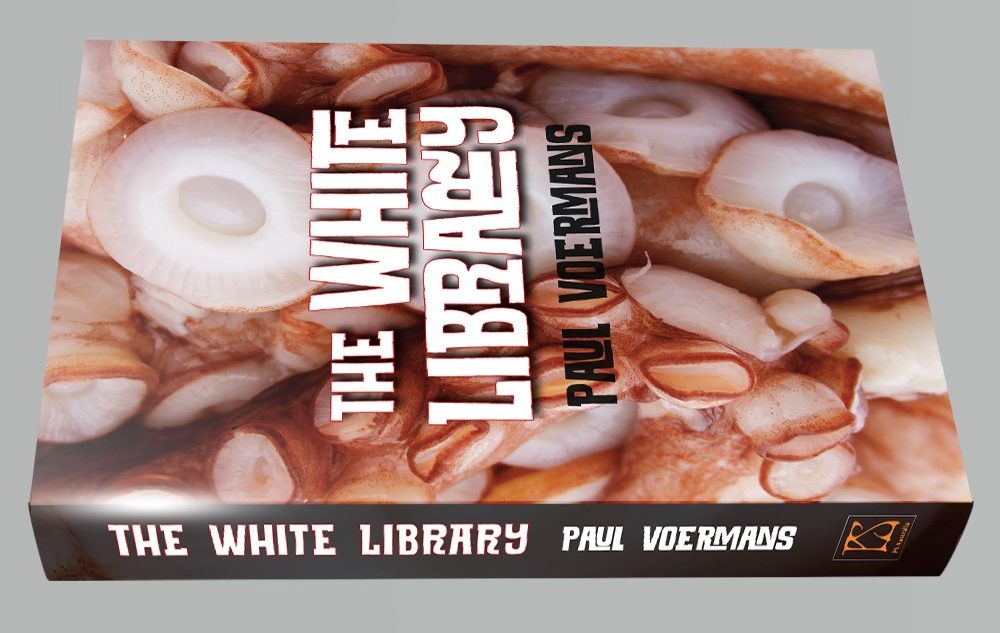

My New Novel–The White Library

This morning I noticed that US voting booths look like Star Wars All Terrain Scout Transports.

This news is a climb down from yesterday’s buzz: I am so pleased to announce The White Library is on the PS Publishing website! You can pre-order here hopefully in time for Christmas. Do get the lovely print edition.

Way down at the end of this kind of long post is the excerpt they published in the PS Newsletter. I have to say I’m pleased with the design and editing process. I have to thank everyone involved, especially at this time of our collective and private lives, to get this out at all. And I’m so impressed by the sheer energy of the PS folks, with so much going on there.

The White library is a novel on one level about the Dotcom explosion. It’s a science fiction story of course, so bears little resemblance to the real State Library of Victoria, or the people there, or what went on there in the nineties.

Except for the excitement.

Dotcom? State Library? Well, yes. Now, it seems weird to have thought that the internet might not change the world if not promoted. If you could connect all the information around the world and use it to help people it needed organisation and collection, nurturing, so a library of course was a good place to start. It’s still a good place. Back then, I was the proud possessor of a 2400 baud modem and a 486, upon which I marvelled at the Bodleian Library’s illustrated manuscripts as they downloaded for 20 minutes an image.

From the other side of the world!

I volunteered for the only Australian website I could find, which turned out to have been published on a Mac Classic on Gary Hardy’s desk (or perhaps under it) at RMIT. A friend told me about it and when I browsed there with Netscape 0.98 the site had crashed. No matter.

The site was VICNET and turned out to be a joint venture soon after housed at the State Library of Victoria. I was the second volunteer. First was Carey Handfield, well-known SF fan and publisher at Norstrilia Press (where I first saw print, along with Greg Egan and early work by Gerald Murnane). We stood before goggling community groups trying to make real the concept that computers could be joined to one another in some kind of web.

When a job opened up there I showed up with my HTML of the VICNET website on a floppy disk, no matter that I was no designer and that it slowed the page loading, a real issue back then. I became a modem whisperer and in the end a more or less genuine tech. VICNET was one of two commercial ISPs in the country, eventually developing a budget and contracts measured in millions of dollars. Thanks to its founders Stuart Hall and Gary Hardy, Adrian Bates and Indra Kurzeme (three out of four of whom are librarians), it established the concept of free internet in libraries; it built and crashed Wi-Fi and broadband and databased websites and site searches; it confronted web filtering and censorship, content moderation, and cyber security–all for the first time.

VICNET grew into the biggest and most popular website in the country by giving sites away, designing them on behalf of the organisations, and roaming the state showing the contents to other groups. (The elderly were particularly responsive.) That there was any Victorian content at all was down to us. We published the first sites for the Melbourne Comedy Festival, The Age, The Department of Premier and Cabinet, The Council for the Ageing, The Australian Grand Prix, Readings Bookstore (I developed a version of the legendary front window which advertised shared houses), 3RRR shows, and a host of our own inventions that we convinced the Thatcherite State Premier and Treasurer, Jeff Kennett and Alan Stockdale to sponsor, sites like MC2 and Skills.net which basically invented web-based social media. (Not that we would want to take credit, but it was all happening in many places at once back then and features fed from one place to another.)

I started a site called Post-paid Poetry, where people sent money (to a PO Box!) if they liked a poem and wanted to support. I wrote the first databased ancestry website, at least in the country, possibly anywhere. I also devised an intranet, for my sins, in order to track knowledge and customers in what would now be something like SalesForce. Back then we called it the Duck Database, for its duck buttons, and our support website sported the Tip-o’-the-Week for many months: “Socks first, then shoes.”

VICNET was populated by a weird menagerie of types, from pale programmers to garrulous unionists to atypical librarians (is there a type? not really), growing from four to over sixty before it was destroyed for basically ideological reasons.

My novel is about so much else besides inventing the internet as we went along. But the friendship and wild business and home jiggery pokery of those days is a strong part of it. The single-mindedness necessary for creativity, too. It’s a novel, which in my fairly naturalistic style has people in it I hope are believable, even if the incredible is its air and poetic imagination its soil. These are the people, in all their variety and imperfection, necessary to bring something new into the world.